|

It's a well known fact that dyslexics are over-represented in the fields of art and design. But could dyslexics be particularly well suited to permaculture design? Background I recently heard a radio programme about dyslexic students at the Royal College of Art. I was surprised to hear that while 5 - 10% of the general population are dyslexic, around 28% of UK art college students are. This caught my interest for a couple of reasons: firstly I was screened for dyslexia as a child and found to be borderline/positive. Secondly, I've heard anecdotal evidence from fellow permaculture teachers reporting a lot of dyslexics on their courses. So I wondered if dyslexics are similarly over-represented in permaculture, and if so, why that might be. I was fascinated to hear that many dyslexics not only struggle with reading and writing, but with drawing as well. While many dyslexics struggle with reducing complex, inter-related thoughts and ideas into a linear, sequential language (and even more so with written representation of language), some also struggle to reduce complex 3d objects in their mind's eye to 2d representations of them. Digging deeper I did a little more research and found an excellent film by Feargal Ó Lideadha called Left from Write. The film explores what dyslexia is, the things dyslexics struggle with, and most interestingly, some of the advantages that dyslexia can bring, such as an apparently innate ability to see the big picture, strong visual and spatial skills etc. Advantages of dyslexia In the film, John Stein, professor of Neuroscience at Oxford University Medical School and Chairman of the Dyslexia Research Trust explains that dyslexics are often better at "holistic kinds of processing". He goes on "and that's why they make good architects, artists and even entrepreneurs... very often dyslexics are highly creative" In the interview below - The Gift of Dyslexia - Stein explains that there are not only more artists, but also more architects, entrepreneurs and engineers than in the general population. He notes that in these disciplines "you have to have a holistic outlook on life rather than being good at sequential things" and that artists, for example "need to see a whole scene and how all the bits fit together, and dyslexics are much better at that than sequential things". He goes on to challenge the argument that dyslexics must be forced into disciplines like art because it requires less reading, and says that the balance of evidence suggests that they are actually more talented in these disciplines. Later on, Stein also describes cases of famous dyslexics (including Albert Einstein) who were much better at seeing patterns than non-dyslexics. In the next interview - creativity and dyslexia - Stein sets out the theory of why dyslexics tend to be exceptionally good at what he calls "holistic visuospatial processing". Although there is currently insufficient evidence to support it, the theory predicts that during childhood the left hemisphere of most people's brains develops to become specialised at linear sequencing. A side-effect of this is that the left hemisphere's capacity for visuospatial processing is reduced in most people. However, in dyslexics this specialisation doesn't happen, and so both sides of their brains are excellent at the more holistic forms of processing. Dyslexia and permaculture

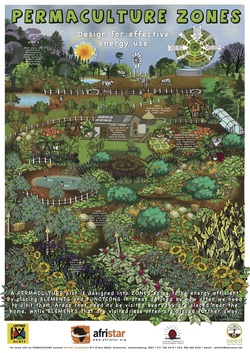

So why might this make dyslexics potentially talented permaculture designers? Well, one of permaculture's axioms is the need to move away from linear thinking and towards more holistic perspectives. As Chris Smaje notes in his article Of Holism and Reductionism: Permaculture and the Science of Hunches: "Permaculture emphasizes holism. It addresses problems through wider relationships and patterns scaled at different system levels, avoiding the reductionism that isolates a problem within a specific sub-system of the wider whole and tries to solve it narrowly at that level only. The science from which it draws most inspiration is ecology, the biological discipline par excellence of relationships, systems, and levels." And of course, permaculture designers are often working in the real world, designing places and spaces, so visuospatial processing is important here, to help designers visualise how a design will fit into a space. And as I have written elsewhere, permaculture makes extensive use of patterns as a design tool. So, if permaculture emphasises holistic thinking, requires visuospatial skills and pattern recognition and application, then surely all dyslexics will be naturally good at it, right? Sadly it isn't that simple. Permaculture design also has sequencing aspects. Designers need to consider the phasing of implementation plans, and design maintenance schedules. A fairly regular criticism of permaculture is that much of the technical information about it lives in densely written "bibles" like Bill Mollison's Designer's Manual, implying lots of reading for anyone wanting to learn permaculture. And I've heard some dyslexics bemoan the academic langauge used to describe permaculture's design principles: "apply self-regulation and accept feedback"; Integrate rather than segregate"... And then there are all those latin plant names which, according to botanical convention, should be italicized or underlined, which many dyslexics find harder to read. Designing with living - or otherwise evolving - systems requires the designer to think about how the system will change over time as, for example, trees & plants grow, wild nature interacts with our systems and so on. It requires, if you will, visuospatial-temporal processing. And It is less clear whether there's been any research into this. Also measuring & surveying, estimating quantities, calculating rainwater storage capacity etc. can be extremely challenging for people with dyscalculia, which often co-presents with dyslexia. So while superficially, permaculture might seem like a perfect fit for dyslexics, challenges remain for the dyslexic permaculture designer. But perhaps most importantly, dyslexia is diverse: each individual has a unique blend of strengths and weaknesses. While there may be general trends - more dyslexics end up in art, architecture etc. - it by no means follows that every dyslexic person will have the particular strengths and weaknesses to be a great permaculture designer. And yet, with around 35% of my permaculture diploma apprentices identifying as dyslexic, it certainly seems like there's something going on. There is clearly a need for more research. Next Steps I'm interested to see what existing dyslexic permaculture designers think about the relationship between their dyslexia and their ability as designers - if there is a link. And as both a teacher and the Learning Coordinator for the Permaculture Association, I'm keen to explore the implications for permaculture teaching practice. So, I've set up a simple survey to explore these questions. If you're dyslexic and practicing permaculture, or if you're a professional who works with dyslexics, I'd love to hear from you. Please visit my survey here. It only takes a few minutes. The first results of this survey will be the subject of my next blog post. Learn More Dyslexic learners in the UK generally report very positive experiences of permaculture design courses. However, I'm designing and running an explicitly Dyslexia Friendly Permaculture Course in September, with the aim of supporting these learners even more. It will be based on the findings from the survey and other research I've been conducting into dyslexia and learning. And the feedback from learners on that course will be fed back to the UK permaculture teaching community to inform practice.

18 Comments

The question "What is permaculture?" appears everywhere in permaculture literature and is often one of the first topics covered on courses. But the question "what is design?" is addressed less often within permaculture circles, and the question "what is distinctive about permaculture design as opposed to other design disciplines?" less often still. So that's what I'll try to do here. What is Permaculture? "Permaculture is a design system for creating sustainable human environments" - Bill Mollison Because this question is addressed at length elsewhere, I won't go into much detail here. Suffice it to say that definitions vary (and are to some extent subjective), but generally converge on something like: permaculture is a design approach with an explicitly ethical basis, that draws lessons from nature to address human problems. What is Design? "Design is a word that's come to mean so much that it's also a word that has come to mean nothing." - Jonathan Ive Like permaculture, the term design is easy to understand but can be tricky to pin down to an accurate but concise definition. It is a word that has been used in myriad contexts, and picked up associated connotations and nuances along the way, obscuring its core meaning. So let's start with the origin of the word itself. Design can be both a verb - the act of designing - and a noun - an artefact that is produced by the act of designing: "design (v.) 1540s, from Latin designare "mark out, devise, choose, designate, appoint," from de- "out" (see de-) + signare "to mark," from signum "a mark, sign" (see sign (n.)). Originally in English with the meaning now attached to designate; many modern uses of design are metaphoric extensions." (Harper, 2015) "design (n.) 1580s, from Middle French desseign "purpose, project, design," from Italian disegno, from disegnare "to mark out," from Latin designare "to mark out"." (Harper, 2015)

The contemporary Oxford Concise Dictionary definition attaches concepts that many designers consider to fundamental to design: an overall purpose (e.g. a brief), function and aesthetics: "design noun. 1. a plan or drawing produced to show the look and function or workings of something before it is built or made. > the art or action of conceiving of and producing such a plan or drawing. > purpose or planning that exists behind an action or object. 2. A decorative pattern. verb. decide upon the look and functioning of (something), especially by making a detailed drawing of it. > do or plan (something) with a specific purpose in mind." (Pearsal, 2001)

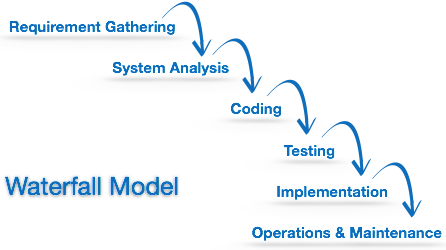

Design Processes "I tried a dozen different modifications that were rejected. But they all served as a path to the final design." - Mikhail Kalashnikov Rational Model Traditionally, many design disciplines have identified a logical sequence of discrete stages involved in progressing from the problem identification to a finished solution. Newell & Simon (1972) call this the rational model. It usually starts with a brief or problem and may incorporate research, analysis, prototyping, testing, (at this point many iterations or the prototype may be developed tested, modified/improved and retested), presentation, implementation and maintenance/evaluation stages. Each stage of the overall design process has processes and tools associated with it, and it may have professional standards, codes of practice and even statutory regulation/legal constraints. Examples of the rational model include the RIBA Plan of Work in architectutre & construction, the waterfall model in SDLC (Software Development Life Cycle) and SSADM (Structured Systems Analysis and Design Method) in information systems design. Some structured design processes incorporate an iterative, or cyclical prototyping phase, where numerous candidate designs are tested and tweaked based on the test results until the final design is ready. Action-Centric Model The Action-centric model recognises that designs often progress in a non-linear fashion, that designers may work more spontaneously and intuitively, sometimes jumping backwards and forwards between design stages, and that design goals may evolve during the process. While this model lacks the structure that can help to ensure that essential tasks & processes are carried out, it is more flexible, can enable spontaneity and creativity, and accommodate more opportunistic design responses. Clearly, some design disciplines will lend themselves to more formal design processes and others to more fluid ones. And even within a given discipline, different design projects may call for different approaches. This is particularly so for permaculture designers, as they may be designing in various different contexts, as we will see below. In such cases, it can be a real challenge for the designer to identify the appropriate approach for any given problem. So, what's distinctive about permaculture design? So far we've looked at some general aspects of design. But what is it about permaculture design that makes it permaculture? Explicit Ethics While many professional disciplines such as medical and legal professions have a strong guiding code of ethics, this is often less present, or emphasised as much in traditional design disciplines. Architects in America, for example, could be faced with with the moral question of whether to accept a commission to design a prison that contained an execution chamber, with little solid guidance from their profession. And then there's the environmental destruction caused by mining & processing building materials, emissions from buildings' energy systems and so on. In contrast, permaculture's simple ethics are placed at its very core. They're clearly set out in Permaculture: A Designers Manual (Mollison, 1988). Briefly, they comprise:

If the design isn't aiming to work in accordance with these ethics, it ain't permaculture, plain and simple. A thousand herb spirals on the lawn of your nuclear missile launch facility aren't going to make it a permaculture nuclear missile launch facility. Democratic design: participatory & collaborative "No one has to be a genius, but everybody has to participate" - Philippe Starck The complexity of many modern design challenges demands that the people who meet them know what they're doing: buildings need to stand up; the software that runs artificial ventilation machines needs to be bug-free; the wheels of trains, cars, buses and bicycles need to stay on. But we live in the age of the superstar designer. Fashion designers, architects, furniture designers enjoy the same levels of fame and celebrity as film stars, sports personalities and musicians. In a consumerist culture, we idolise those who conceive the objects we worship. And this creates a kind of debilitating mystique, a learned helplessness around the business of designing. We've come to regard the art of design as something reserved for highly trained people who posses a genius that the rest of us can only dream of. When it takes seven years to train as an architect (and arguably a lifetime of pratice to become a really good one), how can the rest of us ever presume to design anything? But not all designing is highly complex, or a matter of life or death. Not all designing requires expert-level knowledge. Not all designing needs to be the sole preserve of technical or creative specialists. Some design can be carried out by the masses. Some design can be democratic. The notion of democratic design is not new. Philippe Starck's definition of democratic design is design that provides quality pieces at accessible prices. In this definition, design authority continues to reside with the expert - i.e. Starck - while the rest of us get to participate by spending money on goods he's designed. We are still passive, helpless consumers. In contrast, permaculture's notion of democratic design is about people taking control of the design process itself. And where possible, implementation and production processes too. As Herbert Simon notes: "Everyone designs who devises courses of action aimed at changing existing situations into preferred ones." And it is this broader definition of design that, I think, applies to permaculture. Indeed, if we accept Bill Mollison's 'prime directive' of permaculture, that "The only ethical decision is to take responsibility for our own existence and that of our children" (Mollison 1988), it could arguably be more accurately described as anarchic or libertarian design. Of course, good design requires skill, judgement, and an understanding of design principles. And the more one practices design, learns from others and reflectively develops one's practice, the more successful one's designs will be. And so, permaculture invites us all on a journey to explore our own creativity, develop our design skills, reflect on our success and failures, and deepen our thinking. Biomimetics... or "Ecomimetics"? A core idea in permaculture is that biological and ecological systems provide us with useful examples of successful strategies as well as solutions to specific problems that we can use in our own designs. There are, of course, other disciplines that look to nature for inspiration: "Biomimetics (which we here mean to be synonymous with ‘biomimesis’, ‘biomimicry’, ‘bionics’, ‘biognosis’, ‘biologically inspired design’ and similar words and phrases implying copying or adaptation or derivation from biology) is... a relatively young study embracing the practical use of mechanisms and functions of biological science in engineering, design, chemistry, electronics, and so on" (Vincent et al 2006) So, permaculture could perhaps be described a biomimetic design discipline. However, the story doesn't quite end there. Because permaculture places a particularly strong focus on systems thinking, it tends to look to ecosystems for much of its inspiration. As ecosystems include both biological and non-living elements, permaculture might more accurately be described as an "ecomimetic" design discipline.

Pattern application seeks to identify patterns in nature, and understand what they convey to us about the function of the system in question. When we want elements in our designs to perform certain functions, we can choose appropriate patterns to achieve our ends. For example, trees follow a branching pattern because it is an efficient pattern to transport water and sugars around. If we want to design a garden with an efficient path layout, we may find that a branching patterns is the most appropriate or useful.

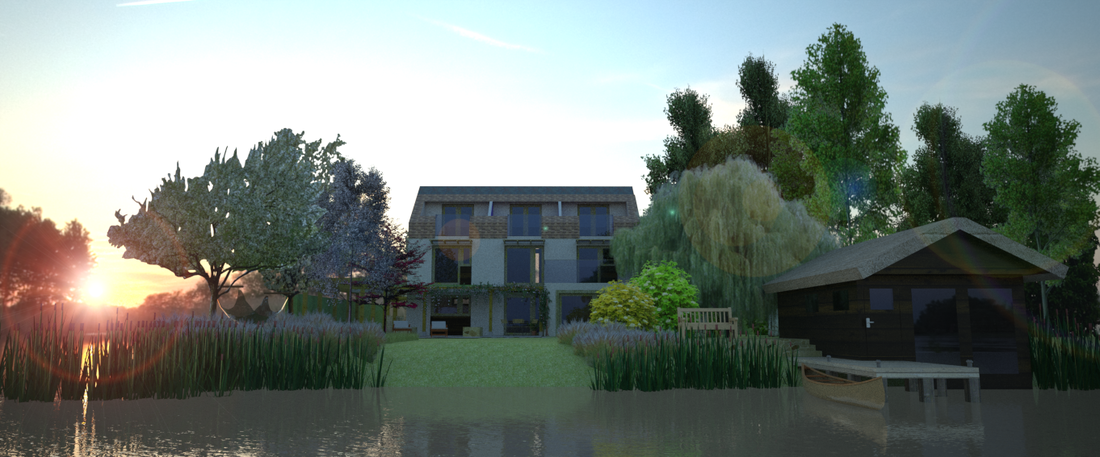

So, an architect could use the permaculture design philosophy to inform their design for a building or neighbourhood, such that the final development exhibited sustainable, regenerative and resilient qualities. Equally an IT systems designer could use permaculture design to choose to deploy recycled or energy efficient computers in a resilient architecture, perhaps running open source software. Design processes There are a number of design processes that have been put forward by people through permaculture's history. Typically they've been borrowed and/or adapted from other disciplines and many of them propose a sequential approach based on the rational model mentioned above. A fairly typical example is SADIMET: Survey, Analyse, Design, Implement, Maintain, Evaluate, Tweak. An interesting exception is the design web which is perhaps closer to the action-centric model. Proposed by permaculture teacher and author Looby Macnamara, the design web proceeds in a non-linear way between 'anchor points' within a wider process. For a comprehensive review of design processes and an exploration of their origins, look at James Taylor's excellent slides on the subject.

Summary So, there you have it in a nutshell. Permculture design is about giving yourself permission to take control, arrange things in ways that work with nature to achieve effective and ethical results. It's about working smarter, not harder, and you can apply it in almost any context. And most importantly, it's about enjoying yourself while you're at it. References/Bibliography

Diamond, J. (2006) Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed. Viking Press, New York. Harper, D. (2015) Online Etymology Dictionary [Internet] http://www.etymonline.com [retrieved 23/08/2015] Holmgren, D. (2002) Permaculture: Principles & Pathways Beyond Sustainability. Holmgren Design Services, Hepburn. Mollison, B. (1988) Permaculture: A Designers Manual. Tagari Publications. Newell, A. & Simon, H. (1972) Human problem solving, Prentice-Hall, Inc. Orr, D. W. (2002) The Nature of Design: Ecology, Culture, and Human Intention. Oxford University Press, Oxford. Pearsall, J. (Ed) (2001) The Oxford Concise Dictionary, Oxford University Press, Oxford. Starck, P. (2015) [Internet] Quotes http://www.starck.com/en/philippe_starck/quotes/ [retrieved 07/02/2016] Vincent, J. Bogatyreva, O. Bogatyrev, N. Bowyer, A. Pahl, A. (2006) [Internet] Biomimetics: its Practice and Theory http://rsif.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/3/9/471 [retrieved 06/02/2016] Whether you think COP21 was an historic success or a catastrophic failure, much remains to be done on the ground to avert the worst effects of climate change. Fortunately, there are some simple land management techniques that can have dramatic effects and could lead to a prosperous and sustainable future for all.

1. Farmer Managed Natural RegenerationA cheap, fast and simple way to reforest landscapes and reverse desertification. Often more successful than tree planting projects, over 50 million hectares of Niger have been reforested this way, adding $200 per year to farmers' incomes in the process. 2. KeyLine Design Careful water management in the landscape can help to reduce the effects of floods and droughts, while building soil fertility, improving yields and locking up carbon. 3. How to Restore A Rainforest What started as an orangutan conservation project became a model for restoring devastated rainforests. Because the project provides secure livelihoods for local people, they became protectors of the restored forest. 4. Ecological Rehabilitation, Loess Plateau, China The spectacular story of how an area of China the size of France was restored from desert to a lush, green, productive landscape, lifting people out of poverty in the process. 5. How to Green the WOrld's Deserts & Reverse Climate Change How holistic planned grazing of livestock can turn deserts into grasslands, build soil carbon and deliver social, economic and ecological benefits. While working towards my Diploma in Applied Permaculture Design my motivation waxed and waned. In total it took me 6 years to complete it. Here are five ways I found the motivation to finish it off, and some ideas about how you could too.

I eventually realised that for me, the best reason to do the diploma was to actually develop my design skills. From this point, not only did the whole diploma process make a lot more sense, it made me value it more, and it made me realise that the longer I took over it, the more I stood to learn. Paradoxically, this took the pressure off me to finish and allowed me to focus on the learning and enjoying the process. As I started to enjoy the process more, I began to feel that I'd like to help others on the same journey and become a diploma tutor. I was able to visualise myself giving turorials and diversifying my poly-income a little more. Now I really did have an incentive, which focused my mind and allowed me to prioritise diploma work over other things. By really focusing on your own reasons for doing the diploma, identifying the benefits of finishing and visualising yourself afterwards, it can help to keep you on track and keep prioritising the diploma.

This meant that he needed to be observed giving tutorials, performing interim and final portfolio assessments, and running an accreditation event. I realised that if Graham was my tutor, my diploma progress would support his tutor training progress: Graham didn't ask or expect me to do this, but by linking my own progress to his in my own mind, I felt I'd be helping him out by keeping going, and letting him down if I slacked off. This in turn helped to motivate me as I felt somehow accountable to him. Other ways of building in this kind of accountability might be:

3. Get Competitive One permaculture principle promotes cooperation, not competition. But like all principles, there are times when they're helpful and there are exceptions to them. And if we're using nature as a teacher, there are plenty of examples of competition out there, so for me it's a valid permaculture strategy. At the 2013 National Diploma Gathering Graham told me that he'd set a date for two of his other apprentices to hand in their portfolios for their Interim assessments. While I wasn't trying to 'beat' anyone, I didn't want to be the laggard of the group, so I worked hard over the Christmas break to write up enough designs to hand in my portfolio. This in turn meant that I stopped obsessing over the details of the how to format my design write-ups, and allowed me to just get on with it. One way to replicate this effect would be to agree within your peer group to set a date that you're all going to hand in your portfolios. Or at least to set a date when you'll all present a design to each other at a guild meeting.

An additional yield - and therefore incentive - was that I could use my designs to show prospective diploma apprentices the kind of work they might expect to produce and the kind of skills I'll be able to help them with as a diploma tutor. So in this respect, they act like a shop window or marketing tool for me as a tutor. 5. Make the work itself enjoyable

After a long day at the office writing emails and funding applications, the last thing I want to do is come home and write up long-winded design reports. I'd far rather make pretty pictures and lay out pages with nice graphics. And as a picture tells a thousand words, using lots of annotated photograps, drawings and diagrams means MUCH less writing. If the process of creating the portfolio itself feels like an indulgence, you're far more likely to want to do it in your free time. You could do this by thinking about creative processes that you enjoy and make that the basis of (or at least a major element of) your portfolio. Other ways to do this might be use your portfolio as an opportunity to learn a new skill like building a website, making videos, or learning a CAD package. Could we be better at valuing the marginal and integrating a more diverse range of cultures & perspectives into the permaculture community? During the last four years I've help to instigate, co-design, secure funding for, and support the co-ordination of a wonderful project called the European Permaculture Teachers' Partnership (EPT). The aim of the project was to provide a support network for teachers across Europe, many of whom were working in quite isolated conditions. The project was to provide a forum for these teachers to exchange teaching methods & course curricula and see examples of good permaculture practice by visiting local projects. Meanwhile, comparing organisational structures of national permaculture associations & institutes was to provide inspiration & encouragement to those countries that lacked such organisations, so that they would feel better equipped to establish them. Learning materials would be translated to hasten the spread of permaculture in other languages. Finally, a discussion on how to widen participation was to examine questions of how to make permaculture accessible to a wider audience. In effect we wanted to accelerate succession in the European permaculture education ecosystem. The project has been extremely successful. During the two-year funded phase of the project we held a series of seven week-long gatherings; over 150 participants from 23 different countries met with peers and discussed various aspects of permaculture education. Two new national permaculture organisations have been established with a third on the way, a new diploma process has been designed in one country, and an older, less functional one revisited and overhauled in another. One of the partner organisations has gone on to secure further funds for transnational teacher development activities. An Emerging Culture The feedback from participants has been overwhelmingly positive and at times deeply touching, describing how the project has changed their lives for the better, made them feel more connected and how we have created a new family. Indeed, during the project a strong culture emerged that connected many of the participants on a profound level. This culture emerged largely as a result of the contributions of participants, who were invited to facilitate, lead sessions and activities. This was a learning journey for them and I'm deeply grateful to them for their contributions and commend them for their courage in stepping outside their own comfort zones to take up the challenge. This culture was characterised by a lot of standing in circles, sometimes holding hands, often being encouraged to close our eyes and be led in a guided meditation or grounding exercise. At other times, tools from Joanna Macy's Work That Reconnects were used, such as The Milling where participants are encouraged to move around a space making eye contact with others as they pass until they come to a standstill facing someone else. They were then asked questions that encouraged them to share intimate thoughts: "what are your dreams?" etc. Another significant feature of the culture was singing. Often we were all encouraged to sing together, often singing songs in rounds. Sometimes we were led in a call-and-response song where the responsibility to sing the call part passed around the circle, so that everyone had the opportunity to sing solo in front of the group. The final celebration took the form of a ceremony where everyone was asked to walk through a door into a garden: on passing through the door they had water sprinkled on them, and a mud bindi applied to their face. These exercises and rituals are undoubtedly powerful. And they are important tools for those looking to foster deeper connections with others, seeking an inner transition, or hoping to add a spiritual dimension to an experience. However, after reflecting on the widespread use of them in the EPT, I'm left wondering if we should have explored issues of diversity & inclusion, because aspects of the culture that connected many of the participants also marginalised and excluded others. One attendee climbed out of a window to avoid participating in the closing ceremony, another was clearly made to feel deeply uncomfortable when he refused to join in. Later conversations with others revealed that they went along with these activities because of peer pressure, but they found them uncomfortable, embarrassing or just "didn't get it". At other times during the project other people discreetly slipped away when things started to get "a bit too hippy-ish". I also tend to feel uncomfortable with these kinds of exercises, but during the EPT I generally went along with them due in part to peer pressure (more on this later), and in part because I didn't want to damage the confidence of any trainee facilitators by making a big fuss in the middle of their sessions. Even so, on the last night of the project I found myself hiding behind a pile of straw bales to avoid yet another face-painting ritual, and then quietly slipping away to avoid the final party in case there was more of the same. Beyond EPT EPT Participants can be forgiven for bringing this kind of practice into the culture of the project. In the eight years I've been around permaculture I've seen it crop up regularly at various permaculture gatherings and teacher trainings. And some people seem to be integrating quasi-spiritual practices with Permaculture Design Courses (PDC). But again and again I also find myself in conversation with people grumbling about how they feel uncomfortable with - or embarrassed on permaculture's behalf because of - this stuff. Spirituality When I've broached the subject of my own discomfort with the people who are enthusiastic about rituals, group meditation, singing etc, I'm met with a range of responses. Some people acknowledge that these kinds of activities need to be very carefully considered before their inclusion in a programme. But I've also received a kind of knowing, sympathetic look and words to the effect of "Oh, you haven't developed your spiritual side yet". This implies that any truly holistic understanding of permaculture is contingent on integrating some form of spirituality into your life. Having spent many years contemplating my own spirituality and consequently becoming a humanist, I don't agree. I also believe that it's counter to the original intentions of Bill Mollison (a scientist) & David Holmgren (who self-identifies as an atheist in Permaculture Principles & Pathways Beyond Sustainability). As I understand it, the ethics of permaculture were deliberately pared back to a minimal set of values that could be consistent with, and integrated into, almost all major belief systems; spiritual or otherwise. It is inherently atheistic, in the sense that it is not, in and of itself, a religious or spiritual discipline. I believe that the enforced use of symbols and practices (e.g. meditation, grounding exercises) drawn from certain cultural & religious traditions at permaculture courses and events is potentially damaging. By creating an association between permaculture and certain forms of (new age-approved) spirituality, we limit permaculture and undermine its cultural "portability". By borrowing the hallmarks of some religions we potentially exclude others, not to mention the secular: we risk creating a kind of worldview monoculture. Furthermore, the appropriation of religious symbolism & practice potentially carries the risk of offending the very traditions from which they have been drawn by using them in inappropriate, disrespectful or blasphemous ways. To be truly inclusive as teachers & facilitators, I believe that we should keep religion out of our permaculture teaching and credit our students with the intelligence to make their own choices about spirituality. Group Singing When the topic of discomfort about singing in front of a group has been raised, I've been told that "There is evidence that singing reduces stress hormones". And this is true. However, there is also evidence that performance anxiety greatly elevates stress hormones: being coerced through peer pressure into singing in front of an audience of 50 people can be deeply traumatic for some people. As teachers, I feel we should give deep consideration to when (and whether) it is appropriate to create situations where people are required to sing on front of others. Loosen up! Finally I encounter a kind of tacit judgement that I'm just a bit uptight and would benefit from loosening up a bit. I admit that this is true to some extent. But while I identify as middle class, liberal and open minded, this is in the context if my cultural background: Yorkshire in the north of England. We are socially conservative, repressed and proud of it. We have a long tradition of deeply reserved behaviour, understated compliments, adversarial humour and muttering sarcastic comments into our beer. And to be honest, I'm fine with that. I have no cultural frame of reference for holding hands in a field "feeling the energy go through my feet and into the earth". When I'm cajoled into these kinds of activities I feel utterly inauthentic, like I'm betraying my true identity and pretending to everyone around me. Making me participate in these activities makes me more uptight, not less. And there are plenty of folks who are a lot more uptight than me! Privilege & Marginalisation Being a white, middle class man from Western Europe I am profoundly privileged. How can I possibly claim to feel marginalised? Well, that's kind of the point: if someone as privileged as me can feel this marginalised, who else is being marginalised but doesn't feel as empowered as me to speak up? How about people who are introverts or chronically shy? I've had students tell me how relieved they were that the PDC we'd just taught wasn't full of "happy clappy stuff" because it would have made them leave the course. I've had another student tell me that they went through a living hell during what seemed to me a to be a completely innocuous ice-breaker exercise on the first day of a PDC. And how about people from other cultural backgrounds? There are countless other cultures that are far more reserved and socially conservative than us Yorkshire folk. And it seems that those of us who are uncomfortable about this stuff are in good company. An experienced British permaculture teacher recounted a story of a similar exercise at an International Permaculture Convergence many years ago. He was standing in a circle next to Bill Mollison. When they were told to hold hands Bill turned to him and muttered "load of fucking woo-woo". And yet those of us who feel marginalised and excluded by these practices seem to keep going along with them. And those who promote them don't seem to "get" how others feel about it. Why? Well, I have a theory that goes something like this... Peer Pressure: Obedience & Conformity In group situations, most people surrender a great deal of power to the leader, be they a 'superior' colleague, a teacher, a facilitator, or other figure of authority. As the famous Milgram Experiment shows, most people have a strong tendency to obey authority figures, even if they are instructing them to take actions that are completely at odds with their internal ethics and morals. On top of our tendency towards obedience, we have a strong propensity to conform to group behaviours. Famous examples showing this include the Asch Experiment, the Smoke Filled Room Study and a clip - "Groupthink" - from the US T.V. show Candid Camera. What I find interesting in all of these examples is the degree of discomfort that the subject feels during the process. The situation places them in a state of cognitive dissonance between what their senses, ethics, beliefs and reasoning tell them and the signals received from superiors and/or the behaviour of the group. For many, the easiest way to reduce the dissonance and discomfort is to obey or conform: the alternative is to choose potential conflict with an authority figure or with a group: unfavourable odds. As teachers and facilitators this gives us an incredible amount of power in group situations. And with this power comes a great responsibility to care for the people in our charge. Ambiguous Feedback Signals I would hope that any professional permaculture teacher or facilitator who is serious about their practice would apply self-regulation and accept feedback. So why don't the people who are placing others in such discomfort seem to be doing so? One would think that a participant climbing out of a window to avoid an activity is a pretty clear feedback signal. But I'm not so sure. If a facilitator has personally derived a great deal of benefit from the kind of exercises outlined above, they're likely to be positively disposed towards the activity, and be keen to share them: "I found this really powerful and beneficial, so I'd like to share with others so they can benefit too". Their starting position about the activity is positive, and due to confirmation bias, they're likely to interpret feedback that does come to them in a way that confirms their starting position. And if they haven't personally experienced discomfort around this kind of activity, the likelihood of someone else being uncomfortable is much less likely to be on their radar: they aren't looking for negative feedback. If they're leading an activity with a group of 50 people, their adrenalin is likely to be high. They're thinking about what to say next; is what they've planned going to work? What's the weather doing? Are the group doing the task correctly? A myriad of questions and thoughts run through the facilitator's mind. The people who are a bit uncomfortable, but go along with the activity out of peer pressure are not necessarily outwardly giving a clear feedback signal; certainly, any signals that they do give may be too subtle for the facilitator's distracted and adrenalin-drenched brain to pick up on. Those who quietly slip away are not even visible. If the vast majority of the group seem to be going along with the activities and joining in, the feedback signal is overwhelmingly positive and reinforcing. In the absence of clear, unambiguous feedback signals, the facilitator is understandably likely to miss the fact that they've unwittingly made a number of their participants uncomfortable, that they've potentially alienated and excluded members of their group. But this is part of the challenge of truly welcoming diversity and creating a genuinely inclusive culture. To do so we must be wary of the danger of confirmation bias, cultivate empathy and actively invite - and deeply engage with - critical feedback and different perspectives. Summary

Hopefully, the EPT has provided a safe space for people to try out their teaching and facilitation techniques. As teachers of permaculture, any EPT participants that did feel uncomfortable during these exercises are already very much "bought-in" to permaculture and are probably used to seeing some of this stuff. No real harm has been done. But what about those people on the edges of permaculture: those we wish to invite in? What about PDC course participants that EPT participants are going to be teaching? Should teachers use any of these methods and activities on introductory courses or PDCs? If we're serious about living permaculture ethics of people care, and principles of integrating as diverse a range of people as possible into the permaculture community, I think we really need to pay attention to the feedback we receive from those people at margins. My plea to teachers and facilitators is this: If you're going to perform rituals, conduct group meditation, use techniques like those from The Work that Reconnects, or compel people to sing, please make these activities genuinely optional: be absolutely clear about what you're offering and what it entails, and be absolutely clear that it's absolutely OK to not join in. Better still, avoid putting people in uncomfortable situations by making the default option non-participation. Make it so that people who want to do this stuff have to actively choose to do it, rather than putting people in a situation where they feel they have to climb out of a window, hide behind straw bales or quietly slip away. Reflection Questions Here are some questions around inclusion that all teachers & facilitators might find useful to reflect on: What might it feel like to have a group leader and a group of people encouraging you to do something that makes you feel uncomfortable? Have you ever gone along with something that didn't agree with because the group encouraged you to do it? How did you feel about yourself afterwards? Have you ever taken an individual stand against a large group of people? How might it feel? Have you ever been excluded from a group? How did that feel? How could you develop your practice to avoid excluding people? Is a permaculture course or event the right place for spiritual practices or exercises designed to create deep connection? |

Details

AuthorPermaculturist, Archives

May 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed